Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow: Part 1

This weekend Britain celebrates the Diamond Jubilee of our Queen, Elizabeth II. It therefore seems appropriate that my posts this weekend are about the visit of her Tudor namesake and ancestor, Queen Elizabeth I, who progressed through the town of Great Dunmow in the Summer of 1561. This was mere 20 months after she became Queen on the 17th November 1558 – her East Anglian progress was of vital importance to convey her image of royalty to her subjects.

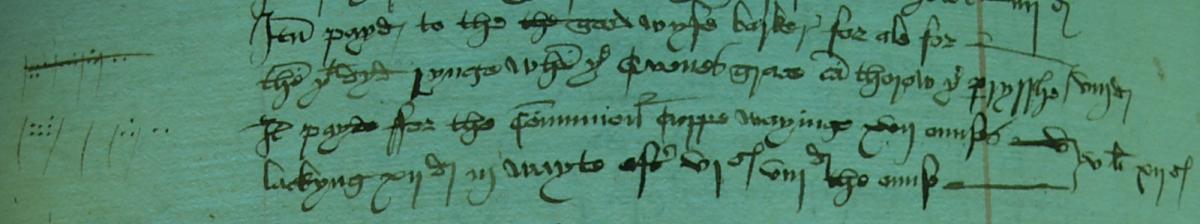

There is only one very brief reference relating to Queen Elizabeth I’s 1561 visit to Great Dunmow within the Tudor churchwardens’ accounts.

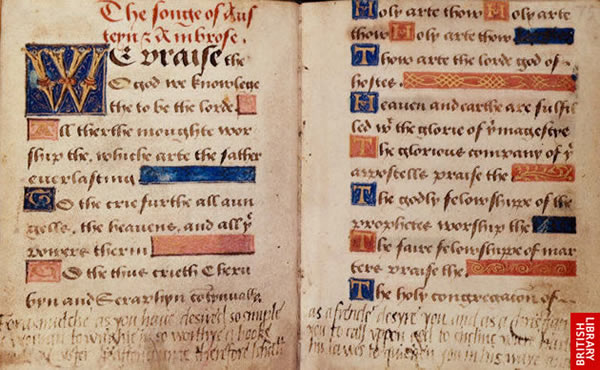

[Itm payd to the the good wyfe barker for ale for those yet dyd rynge when ye Quenes grace cam thorow ye parysshe 8d] Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts – folio 45v.

[Itm payd to the the good wyfe barker for ale for those yet dyd rynge when ye Quenes grace cam thorow ye parysshe 8d] Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts – folio 45v.

Previous records from the churchwarden’s accounts show that the going rate in the 1520s for a day’s labour for a man was about 4d to 6d. So the bell-ringers of the church of St Mary the Virgin, Great Dunmow, consumed the equivalent of nearly 2 days wages in ale! This must have been some celebration…

Unfortunately, no other record survives of Queen Elizabeth’s progress through the town – the church records have no other details. Elizabeth’s half-sister, Mary, had granted Great Dunmow borough status in 1555. Therefore, any expenses that the town incurred during Elizabeth’s visit would have been entered into the borough records – which have not survived.

However, by examining the primary and secondary sources on Elizabeth’s Summer Progress of 1561, it can be stated with considerable certainty that she progressed through the town sometime during the day of Monday 25th August 1561. Elizabeth had been a guest at the home of Lord Rich at nearby Leez Priory 21-25 August; and then stayed at Lord Moreley’s estate in the Hertfordshire village of Great Hallingbury on the night of the 25th. Therefore, she must have come through Great Dunmow sometime during the day of the 25th.

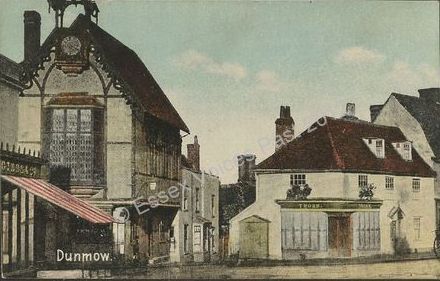

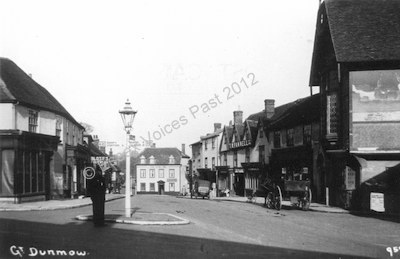

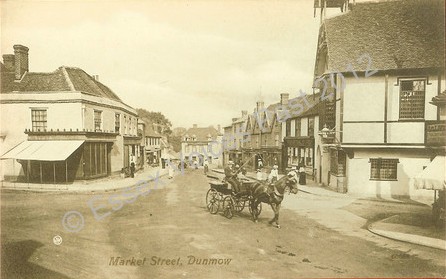

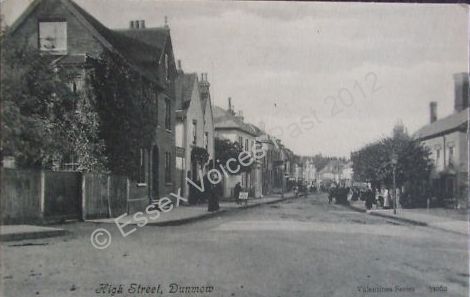

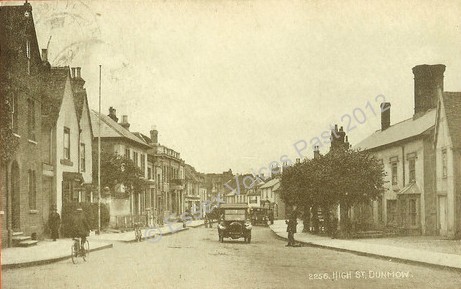

Her route would have been along the Roman Stane Street (now known most romantically as the ‘Old A120’) from Leez Priory to Great Dunmow and then through the town’s High Street. My map of Tudor Great Dunmow illustrates her likely route through the parish. The postcards below show Great Dunmow in the early 20th Century – the Edwardian High Street of Great Dunmow looks very much as it does now. (Tudor town hall on left of 1st two postcards and on right of next 2.)

Many of today’s shops in Great Dunmow originate from medieval and Tudor houses. Therefore, the town of Great Dunmow probably looked very similar 400 years previously in the Elizabethan era. The Town/Guild Hall was built during the 16th century so was probably there in 1561 when Elizabeth progressed through the town. The pale (white) double-roofed building 2nd from the left in the two postcards below is thought to have been a pre-Reformation Catholic priest house which served the town’s small pre-Reformation Chapel. This Chapel was probably closed and destroyed as part of Edward VI’s reforms but it’s priest-house remains and is now a clothes shop.

The town must have extensively and jubilantly celebrated their Queen’s progress. Was there the equivalent of today’s bunting and streamers be-decking the streets of Tudor Great Dunmow? How did the ordinary towns-folk of Great Dunmow celebrate the exciting event of their monarch’s presence in their town?

‘Every spring and summer of her 44 years as queen, Elizabeth I insisted that her court go with her on ‘progress’, a series of royal visits to town and aristocratic homes in sourthern England. Between 1558 and 1603 her visits to over 400 individual and civic hosts provided the only direct contact most people had with a monarch who made popularity a cornerstone of her reign. These visits gave the queen a public stage on which to present herself as the people’s sovereign and to interact with her subjects in a calculated attempt to keep their support.’

Mary Hill Cole, The portable queen : Elizabeth I and the politics of ceremony (Massachusetts, 1999), p1.

Griff Rhys Jones, in the BBC’s new series on the Britain’s Lost Routes, has charted Elizabeth’s 1570s progresses from Windsor Castle to Bristol. Rhys Jones re-enacted the queen’s progress with modern-day people and their cars. He states that accompanying the queen were

– Court Officers

– Ladies in Waiting

– The Privy Chamber and the Privy Councillors

– Servants

– Other ranks

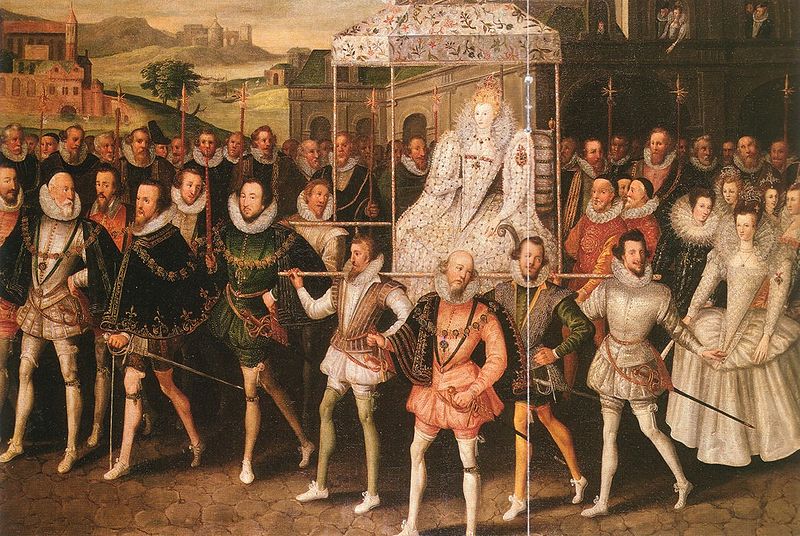

All told, according Rhys Jones, there were 350 people in hundreds of wagons, carts and on horseback. The whole procession was about one mile in length and included all that a fully mobile queen required – from her kitchen to her court documents. This procession travelled at approximately 3 miles per hour as it wound its way through the Elizabethan countryside. The queen often rode ahead of this procession in the type of litter shown in the first picture above. But before her went her ‘Habingers’ who rode ahead to prepare her subjects (and her hosts!) for her presence.

The distance from Leez Priory to Great Dunmow is approximately 6 miles – so it would have taken Elizabeth’s procession two hours just to get to the town. After that was her slow and steady progress through the town. It must have been a day of great celebration for the townsfolk of Great Dunmow! Do watch Griff Rhys Jones’ Britain’s Lost Routes about the west country progress of Elizabeth to understand how she might have progressed through Essex and Suffolk in 1561.

Images

– All postcards on this page are in the personal collection of The Narrator and may not be reproduced without permission.

– Procession portrait of Elizabeth I of England (Robert Peake the Elder, 1551–1619).

– ‘A hermit sitting outside a tavern drinking ale; the alewife approaches him with a flagon’ from Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria (the ‘Smithfield Decretals‘), (France, last quarter 13th century or 1st quarter 14th century), shelfmark Royal 10 EIV f.114v, (c) British Library Board.

– John Nichols, The Progresses & Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth, (London, 1788-1823).

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

You may also be interested in the following:

– Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow: Part 2

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Elizabeth I

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

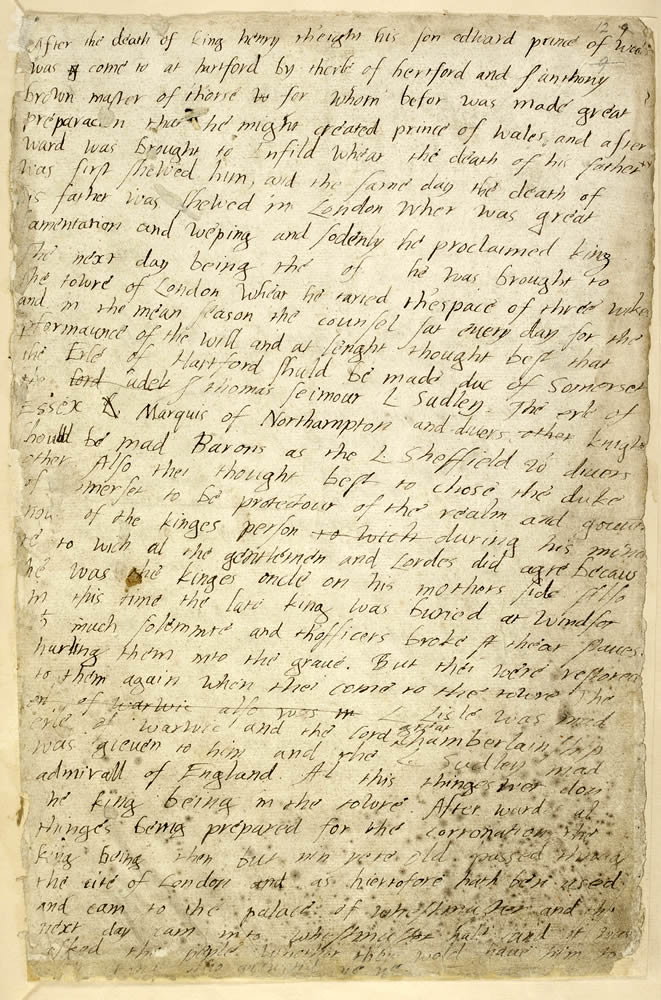

Edward VI’s diary

Edward VI’s diary Frontispiece with the arms of Edward VI, Shelfmark: Royal 16 E XXXII f.1v,

Frontispiece with the arms of Edward VI, Shelfmark: Royal 16 E XXXII f.1v,