Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow: Part 2

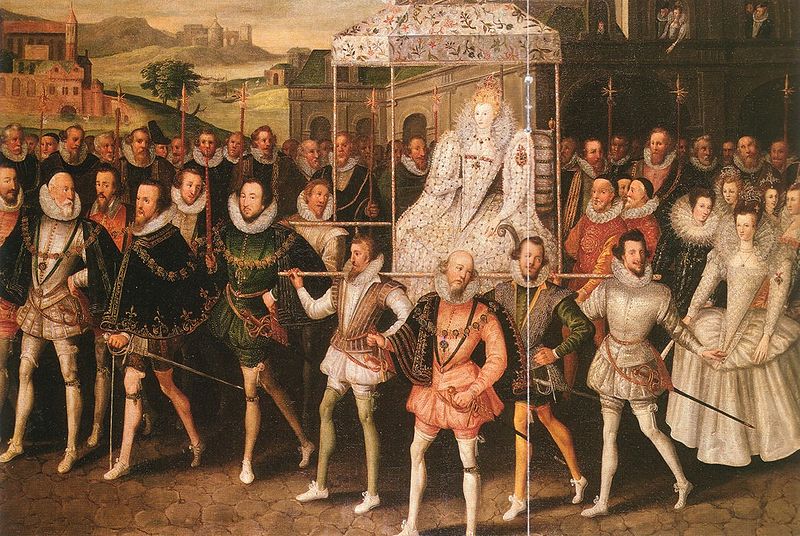

My post on Elizabeth I’s visit to Great Dunmow discussed Elizabeth’s summer progress through the town on 25th August 1561. Today’s post is about the route she took and the houses she visited that summer.

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569),

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569),

shelfmark G.12188, © British Library Board

Mary Hill Cole ‘s book The portable queen : Elizabeth I and the politics of ceremony (Massachusetts, 1999) lists the hosts and their houses visited. Looking at that list today, the venues now read as a who’s-who of 21st Century wedding venues and independent/private schools! I myself married at Layer Marney Towers (nr Colchester). It’s interesting to note that many of those hosts were descendants of Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich, that arch-villain of Tudor history.

– London (Robert Dudley), 24 June 1561.

– Charterhouse, London (Lord North), 10-14 July 1561

– Strand, London (William Cecil), 13 July 1561.

– Wanstead, Essex (Lord Rich), 14 July 1561.

– Havering, Essex, 14-19 July 1561.

– Pyrgo, Essex (Lord John Grey), 16 July 1561.

– Loughton Hall, Essex (Lord Darcy), 17 July 1561.

– Ingatestone Hall, Essex (Sir William Petre), 19-21 July 1561.

– New Hall, Essex (Earl of Sussex), 21-26 July 1561.

– Felix Hall (Henry Long), 26 July 1561.

– Colchester (Sir Thomas Lucas), 26-30 July 1561.

– Layer Marney (George Tuke),around 26-30 July

– St Osyth (Lord Darcy), 30 July to 2 August.

– Harwich, Essex, 2-5 August.

– Ipswich, Suffolk, 5-11 August.

– Shelley Hall, Suffolk (Philip Tilney), 11 August.

– Smallbridge, Suffolk (William Waldegrave), 11-14 August.

– Castle Hedingham (Earl of Oxford) 14-19 August.

– Gosfield Hall (Sir John Wentworth), 19-21 August.

– Leez Priory (Lord Rich), 21-25 August.

– Great Hallingbury (Lord Morley), 25-27 August 1561.

– Standon, Hert (Sir Ralph Sadler), 27-30 August 1561

– Hertford Castle, Herts, 30 August – 16 September.

– Hatfield, Hert (16 September?).

– Enfield, Middsex (16-22 September).

Below is a map of Elizabeth’s route.

© Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

© Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

The cost of the Queen’s progress

The cost to both the Queen and her hosts was extensive. The cost to Sir William Petre of Ingatestone Hall was £136, the Earl of Oxford spent £273 and to Lord Rich at Leighs (Leez) Priory was £389.

At its heart, then, challenge of travel for the royal household was a financial one, because the Queen spent more on food, supplies, and accommodation when on progress than when she remained in the London area….. For the 1561 progress into Essex and Suffolk, Thomas Weldon, cofferer of the household, kept a tally of the Queen’s expenses at each of the places she stayed during the seventy-six day trip. The court’s expenses varied from £83 to £146 per day, with a total cost of £8,540.

J. E. Archer, E. Goldring, and S. Knight (ed.),

The Progresses, Pageants and Entertainments of Queen Elizabeth I

Below are 20th century images of the homes of some of Elizabeth’s hosts.

Layer Marney

Layer Marney

Leez Priory

Leez Priory

Castle Hedingham

St Osyth Priory

Further Reading

J. E. Archer, E. Goldring, and S. Knight (ed.), The Progresses, Pageants and Entertainments of Queen Elizabeth I (Oxford, 2007).

Mary Hill Cole , The portable queen : Elizabeth I and the politics of ceremony (Massachusetts, 1999)

F.G. Emmison, Tudor Secretary: Sir William Petre at Court and Home (London, 1961)

John Nichols, The Progresses & Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth (3 volumes), (London, 1788-1823).

University of Warwick – Centre for the Study of the Renaissance, The John Nichols Project, (2012)

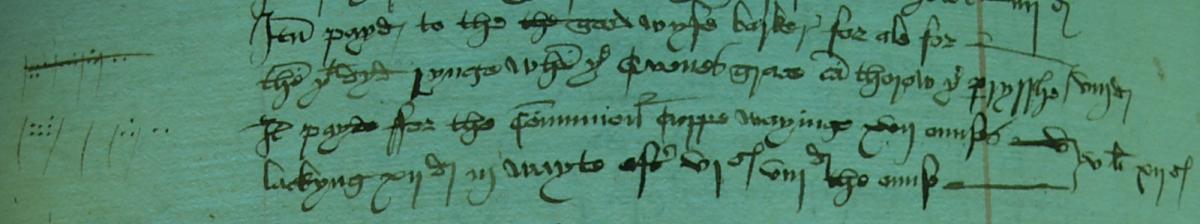

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following:

– Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow: Part 1

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Elizabeth I

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections