Arthur – Prince of Wales

History is full of what-ifs. What if Hitler had been killed in the First World War? What if the weather had been in Spain’s favour when their armada sailed towards England? What-if, what if?

For Tudor England, one of the biggest what-ifs, is… What if Arthur, Prince of Wales, eldest son of Henry VII and his wife, Elizabeth of York, had not died at Ludlow Castle in 1502? Arthur, so named after that most legendary of English kings, and named to herald in a new golden age of anointed Tudor kings. Arthur, that poor half-forgotten boy-husband of early 16th century politics. His marriage and untimely death in 1502 indirectly leading to his younger brother’s break with Catholic Rome and aiding the fuel in the fire of the English Reformation.

On 14 November 1501, Arthur, Prince of Wales and heir to the English throne, married Catherine of Aragon at St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Less than five months later, Arthur was dead having (allegedly) never consummated his marriage to Catherine. In 1509, the newly crowned King Henry VIII, married his brother’s widow and thus cast the seeds of England’s quarrel with the Pope. In the eyes of God, could a man marry his brother’s widow? This was the essence of Henry VIII’s Great Matter – which only troubled his conscience years after his marriage, after he had cast his eyes on the comely Anne Boleyn.

What if Arthur had survived and, with Catherine of Aragon, fathered his own Tudor dynasty?

Arthur, Prince of Wales in c1501; and the young widow, Catharine of Aragon c1502 (by Michael Sittow).

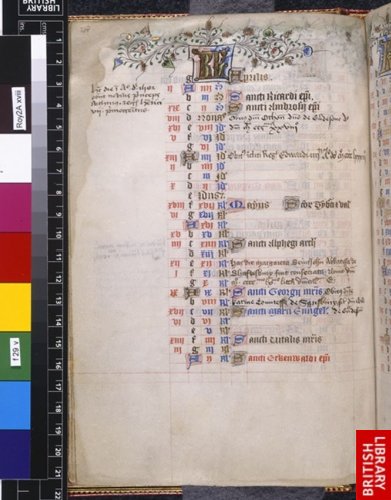

The images below are from the Book of Hours (i.e. prayer book) of Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII and grandmother of Arthur and his brother, Henry VIII. Each page has additional text inserted relating to Prince Arthur.

Calendar page for April with Prince Arthur’s obit (prayers for the dead) added after his death, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f29v, © British Library Board.

Calendar page for April with Prince Arthur’s obit (prayers for the dead) added after his death, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f29v, © British Library Board.

Calendar page for September with additions of the dates of Prince Arthur’s birth and Catherine’s of Aragon 1501 journey to England, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f32, © British Library Board.

Calendar page for September with additions of the dates of Prince Arthur’s birth and Catherine’s of Aragon 1501 journey to England, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f32, © British Library Board.

Calendar page for November with the addition of the date of the marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f33, © British Library Board.

Calendar page for November with the addition of the date of the marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon, from Book of Hours (The ‘Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours’) (South East England, after 1401, before 1415) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f33, © British Library Board.

| Post published: November 2012 © Kate J Cole | Essex Voices Past™ 2012-2019 |

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569),

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569), © Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

© Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

Coronation Oath of Henry VIII with his own annotations (crowned 24 June 1509), shelfmark Cotton Ms. Tiberius D viii, f.89, © British Library Board. (For more information on his changes, see the British Library’s

Coronation Oath of Henry VIII with his own annotations (crowned 24 June 1509), shelfmark Cotton Ms. Tiberius D viii, f.89, © British Library Board. (For more information on his changes, see the British Library’s

Coronation procession of Edward VI along Cheapside, London.

Coronation procession of Edward VI along Cheapside, London.

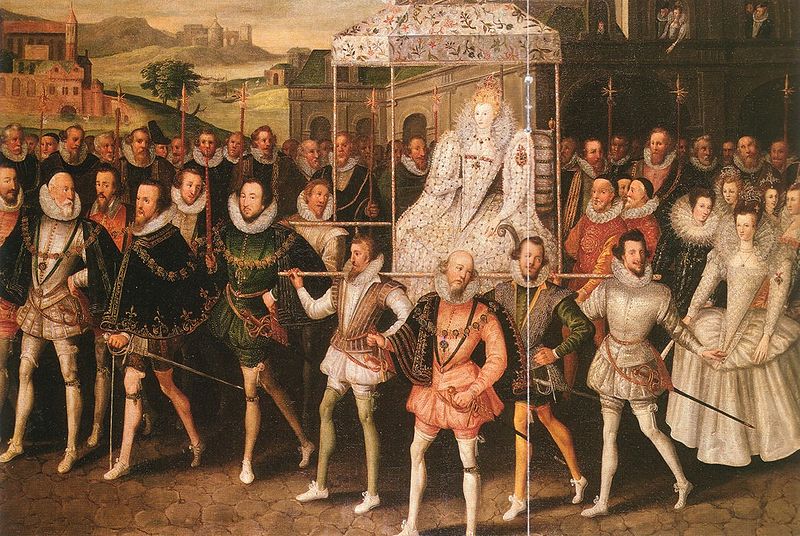

Coronation procession of Elizabeth.

Coronation procession of Elizabeth.

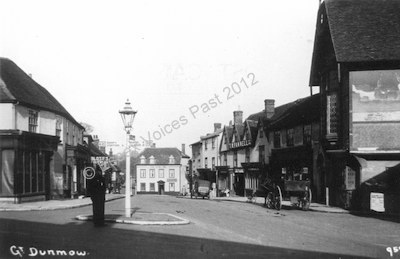

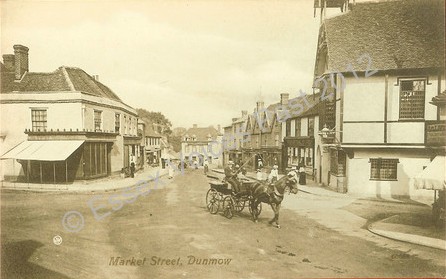

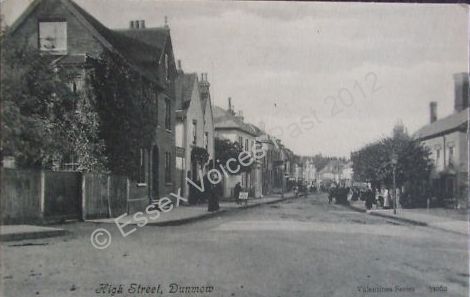

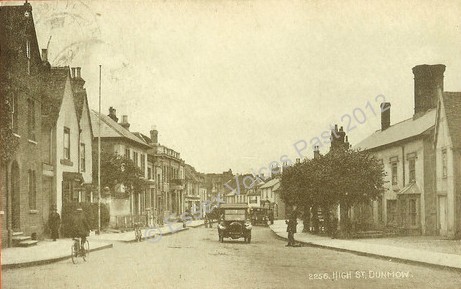

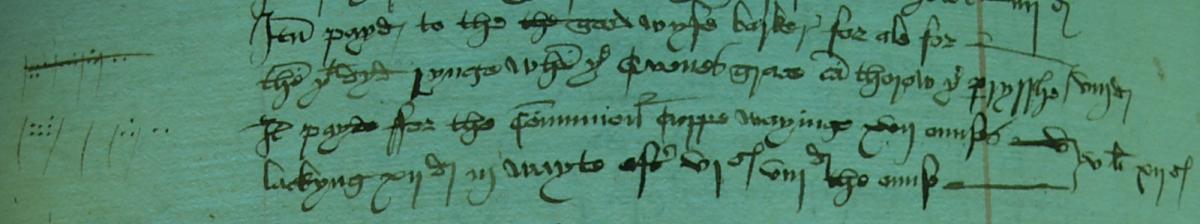

[Itm payd to the the good wyfe barker for ale for those yet dyd rynge when ye Quenes grace cam thorow ye parysshe 8d] Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts – folio 45v.

[Itm payd to the the good wyfe barker for ale for those yet dyd rynge when ye Quenes grace cam thorow ye parysshe 8d] Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts – folio 45v.