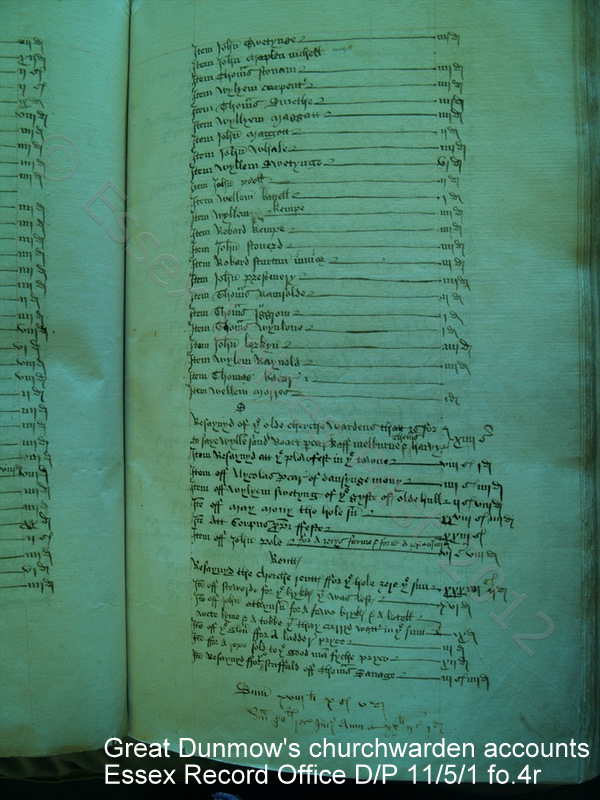

Transcript fo. 4r: The Catholic Ritual Year – Plough-feast, May Day, Dancing Money, Corpus Christi

Transcription of Tudor Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (1525-6)

The top part of this folio has been transcribed here Collection for the church steeple (part 5).

| 23. S [decorative line separator] | |

| 24. Resayvyd of ye olde cherche wardens that is for | |

| 25. to saye wyllia[m] saud[e]r ro[b]art p[ar]car Raff melburne & \Thomas/ harvy | xiiijs |

| 26. Item Resayvyd att ye plowfest in ye towne | viijs jd |

| 27. Item off Nycolas P[ar]car of dansynge mony | iiijs iiijd |

| 28. Item off Wylyem swetyng of ye gyft of olde hall | ijs viiid |

| 29. Ite off may money the hole su[m] | xxviijs iiijd |

| 30. Ite att Corpus Xrsti ffeste | xxiijs |

| 31. Item off John pole \for a yerys farme & for a ??? | vjs viijd |

| 32. Rentt | |

| 33. Resayvyd the cherche rentt ffor ye hole yere ye sum | xxxiiijs ijd |

| 34. Ite off steworde for ye brykke ych [which] was left | xvid |

| 35. Ite off John atkynso[n] for a fewe bryks & a letell | |

| 36. wete lyme & a tabbe ych [which] thay carryd watt in ye sum | ixd |

| 37. Ite off ye glon?? ffor a ladder pryce | iiid |

| 38. Ite ffor a rope sold to ye good ma[n] fyche pryce | xijd |

| 39. Ite resayvyd ffor \ye/ scaffold off Thom[a]s Savage | iijs iiijd |

| – | |

| 40. Sum xviij li xs vd [£18 10s 5d) | |

| 41. Sum ??th rec[eived] ?? Anni xxli ijs jd |

Commentary

There are many interesting pages within the churchwardens’ account-book and this page has to rank high up the list of intriguing pages – not for what it says, but more what it doesn’t say!

The entries on this page are directly after the parish collection for the church steeple so cover the period 1525-6. Therefore, they are the first receipts for money received by Great Dunmow’s church recorded in the leather account-book. Churchwarden accounts or church records for Great Dunmow prior to 1525-6 have not survived. However, several entries on this folio indicate that the previous churchwardens had also kept careful accounts prior to 1525-6.

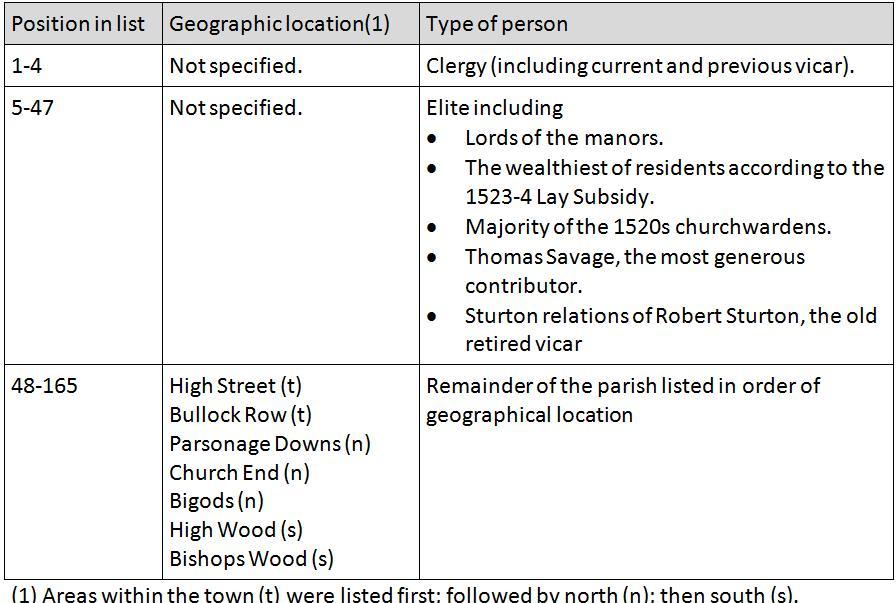

Churchwardens – Line 24/25:

fo.2r recorded that the current (ie 1525-6) churchwardens were Thomas Savage, John Skylton, John Nyghtyngale and John Clerke. This folio records that before them, the previous churchwardens were William Saud[e]r (probably ‘Saunder(s)’ – the churchwardens’ scribe had a soft Suffolk-like accent and didn’t pronounce hard ‘n’s , see The dialect of Tudor Essex), Robert Parker, Raff/Ralph Melbourne, and Thomas Hervy (Harvey?). As Medieval and Tudor churchwardens were often in office for two years, it is likely that these men were churchwardens for the periods 1523-4 and 1524-5. The 14 shillings which the old churchwardens handed over to the 1525-6 set was either their cash-in-hand money left over from their tenure or their own money to make up shortfall in the accounts (or a mixture of both). Medieval and Tudor churchwardens were personally liable for any shortfall in their church’s finances at the end of their period in office. It is because of this personal liability that the accounts of Medieval and Tudor churches were so meticulously documented and recorded.

Plough Monday – Line 26:

The plough-feast was celebrated on the first Monday after the Epiphany (Twelfth Day) in January and was the traditional start to the new agricultural year. The young men of the town dragged a plough from door to door in the parish collecting money. If people did not hand-over money, then a ‘trick’ would have been played on the unlucky house-holder (an event similar to today’s Halloween Trick or Treating). This ‘trick’ was likely to have involved the young men ploughing a furrow across the offender’s land. Money received from Great Dunmow’s plough-feast activities was recorded throughout the Henrician churchwarden accounts. It was likely that this was already a well-established money-making activity for the church within Great Dunmow before this first recording of the event within the leather account-book in 1526. This can be determined by the brevity of this entry which could be interpreted that the churchwardens did not need a full and complete explanation about this particular activity. This was the yearly Plough-Feast – so therefore everyone knew what happened – all that needed to be accounted for was the money received! The churchwardens’ accounts do not record what happened to the money raised from Plough Monday. However, it is likely that the money was used to maintain a ‘plough light’ (candle) within the church. The plough light was one of the many ‘lights’ banned and extinguished by Henry VIII in 1538.

The Wikipedia Plough Monday entry suggests that the Plough Monday customs were revived in the 20th century in the East of England and are associated with Molly Dancers. Below are photographs my son took of the Molly Dancers on New Year’s Day 2012 at The Hythe, Maldon. He’s only aged 8 so the photos are a bit blurry! All photos are copyright of The Narrator, 2012.

Dancing money – Line 27:

Unknown what this ‘dancing money’ was for. Nicholas Parker was one of many Parkers in Great Dunmow but there was only one Parker with the Christian name of Nicholas. In the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy, Nicholas Parker was assessed as having goods to the value of 23s 4d. In the parish collection for the church steeple, he was recorded as living in Bullock Row and paid 8d towards the collection for the church steeple (fo.2v–fo.3r). It was likely that Nicholas Parker collected money on behalf of Great Dunmow’s parish church for ‘dancing’ and gave that money to the churchwardens. The churchwardens were scrupulously thorough in recording which of the many Catholic feast-days money was collected in for the church. Thus, there are receipts for ‘the plough-feast’, ‘Corpus Christi’ and ‘May Day’ on the same page as this entry. As the entry does not specify a precise feast-day or event, it is possible that this was money collected at some type of ‘general’ dance which was associated with the parish church but not connected with any feast-days within the regular Catholic ritual-year.

Old Hall – Line 28:

Unknown what the ‘old hall’ was. It is possible that this was a bequest in the will of a William Sweeting. Unfortunately not many Great Dunmow wills from this period have survived and there is no trace of William Sweeting’s will from this date, so it cannot be established if this was a bequest. (A later blog will explain the reason why there are so few surviving wills in Great Dunmow.) The only William Sweeting to be assessed in the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy had goods to the value of 40s (so was of moderate wealth). However, it is possible that this 1525-6 entry was a gift, rather than a bequest because a William Sweeting is documented regularly in parish collections after this date in the churchwardens’ accounts.

– 1525-6 church steeple collection: William Sweeting lived in Bishopswood and contributed 6d.

– 1527-9 church bell collection: William Sweeting lived in Bishopswood and contributed 5d.

– 1529-30 church organ collection: William Sweeting contributed 2d (dwelling-places not recorded).

– 1532-3 new gild collection: William Sweeting contributed 2d (dwelling-places not recorded).

– 1537-8 great latten candlestick collection: William Sweeting contributed 1d (dwelling-places not recorded).

A William Sweeting, ‘the elder’, was the witness to the 1552 will of Robert Grene(1).

May day – Line 29:

May money 28s 4d. This money received for ‘activities’ held on May-day is a significant amount of money. Records in Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts show that an average daily wage for a labourer was 4d – thus the money raised for May-day equalled approximately 85 days from a labourer. This was a much larger event than the yearly Plough-Feast and received more money. From these scant pieces of evidence, it can be interpreted that the May-day money was collected from possibly the entire parish of Great Dunmow (and probably also other nearby towns and villages – as discussed in later blogs). Again, the shortness of the entry demonstrates that receiving money from May-day was a well-established practice in Great Dunmow by the time of its first entry in the new leather account book of 1526.

This entry does not explain what happened in Great Dunmow on May Day. Wikipedia suggests some of the activities that might have taken place at May Day.

Corpus Christi – Line 30:

Corpus Christi feast 23s. The shortness of this entry is both intriguing and annoying in equal measures! Once again, this was a substantial amount of money, and the briefness of the entry implies that Corpus Christi was a well established feast within Tudor Great Dunmow. Regular Corpus Christi entries are documented throughout the rest of the Henrician Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts. These other entries are much more detailed and thorough, allowing the modern-day reader the most amazing insight into the world of Tudor Great Dunmow and the hierarchical relationship between this small parish and their neighbouring towns and villages. Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi feast, as documented in the churchwarden accounts, has been greatly studied throughout secondary literature on medieval English drama and late medieval religious practices. My own Cambridge University’s master’s dissertation spent over half of the word count discussing and analysing what actually happened during Tudor Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi feast-day. My own account provides an alternative narrative to the explanation provided by other historians (most of whom do not appear to have consulted directly with the original churchwarden accounts nor have walked the streets of the town). As this was such a critical part of my masters’ dissertation, my interpretation of Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi plays will be discussed in detail in a later blog.

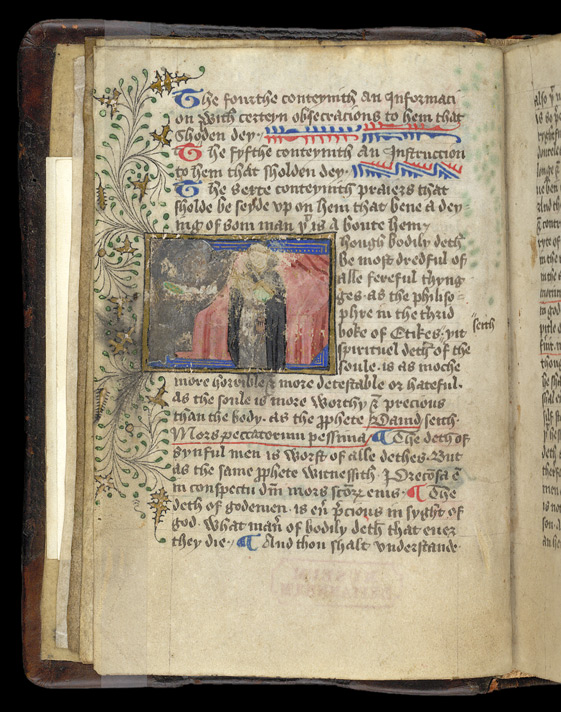

Detail of a miniature of a bishop carrying a monstrance in a

Corpus Christi procession under an canopy carried by four clerics

The Lovell Lectionary. Harley 7026, f13 (England, c1400-c1410),

© British Library Board

Rent of church land – Line 33:

Total rent received in for various church lands. In later years, church rent is fully itemised along with the name of each tenant.

Building materials – Line 34-39:

This part of the accounts is still the receipts (money in) for the period 1525-6. These entries demonstrate that the church (and the churchwardens) were selling items of building materials to some of the townsfolk of Great Dunmow. John Atkinson bought a few bricks and a small amount of wet lime. Mr Fyche (Fitch?) bought some rope, and Thomas Savage bought some scaffolding. This last item by Thomas Savage is interesting for several reasons: firstly Thomas Savage was the man who made the largest contribution towards the church steeple and was ultimately awarded the contract for building the steeple (Henry VIII’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy Tax). Secondly, this entry demonstrates that there were items of scaffolding within the parish church in 1525-6. Either this scaffolding was in the church in the years prior to the building steeple or its existence was because of the construction of the new church steeple. The Victorian vicar of Great Dunmow, W. T. Scott, in his 1873 history of Great Dunmow narrated that there was extensive building work in the church in the years before the church steeple was rebuilt in 1525-6.(2) So there were plenty of reasons for scaffolding to be within the church.

The significance of Thomas Savage’s scaffolding will be discussed in a later blog post.

Footnotes and Further reading

1) Will of Robert Grene, husbandman (March 1552), Essex Record Office, D/ABW 16/83.

2) Scott. W.T., Antiquities of an Essex Parish: Or pages from the history of Great Dunmow (London, 1873) p.20.

For further information on the Catholic religious ritual-year in late medieval/Tudor England, see

– Hutton, R., The rise and fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700 (Oxford, 1994).

For further information on the Plough-feast, see the following websites

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plough_Monday

– http://www.ploughmonday.co.uk/

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– Medieval Plough Monday

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3).

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3). A priest giving communion to a sick man,

A priest giving communion to a sick man,