Reformation wills and religious bequests

Today’s post is about the contents of Tudor wills and how they can be used to inform the modern-day reader about religion during the turbulent reigns of Henry VIII and his three children. The text below formed one of the chapters within my dissertation Religion and Society in Great Dunmow, Essex, c.1520 to c.1560 from my Cambridge University’s Masters of Studies in Local and Regional history awarded to me in January 2012. The text here is in its entirety from my dissertation so reads more as an academic essay rather than a blog post. For this blog post, I have included headings (to break up the text) and images, my original was both heading-less and image-less. If you are wondering why my introduction and conclusion are so short, remember that this is just one chapter in a very lengthy 100 page dissertation and I had a very strict word count to adhere to. The dissertation’s overall introduction and conclusion was far more comprehensive. I have also had to re-arrange the two tables on this post from their original positions within my dissertations – so Table 2 now comes before Table 1. The research of wills I undertook for my dissertation is very different to my normal genealogical research. For genealogical research, I am normally sifting through the personal bequests so to find evidence of family relationships. But for my dissertation, I had to totally ignore family relationships and go for the ‘other bequests’.

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20.

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*- *-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Introduction

Historians have studied the wills of many English parishes to gain understanding about the impact of the Reformation. Eamon Duffy examined the wills of the Yorkshire village of Otley(1) and Caroline Litzenberger, in her analysis of the Reformation Gloucestershire, studied the wills of approximately 8,000 testators(2). Therefore, the analysis of wills is a significant methodology employed by historians to provide evidence for the acceptance (or non-acceptance) of religious changes during the Reformation.

Methodology

The methodology used for this article has been to locate, transcribe and analyse all wills for Great Dunmow for the period 1517 to 1565: 40 wills in total.(3) Litzenberger divided her Gloucestershire wills into elite and non-elite wills, but this division is not possible for Great Dunmow’s much smaller sample. Table 1 and Table 2 displays the results from this analysis and this article examines those results.

Great Dunmow’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy assessments listed 139 tax-payers and 1525-6 church steeple collection listed 165 donations. From these figures, it can be deduced many wills have not survived. Those that have are

- thirty-seven wills proved in the archdeacons’ court of the Commissary of the Bishop of London (originals held by the Essex Record Office in Chelmsford);

- two proved in the London Consistory Court (official copies held by the London Metropolitan Archive in London); and,

- one proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (official copy held by The National Archives in Kew).

The discovery of only two wills proved in the London Consistory Court is particularly disappointing. However, this has been caused because the registers from 1521 to 1539 are missing.(5) Moreover, the first surviving Great Dunmow will that was proved in this court, is from 1559. This demonstrates there are other inconsistencies within the surviving registers from the 1540s and 1550s with the wills for Great Dunmow almost totally missing. Great Dunmow was in the archdeaconry of Middlesex but many nearby towns and villages (for example, Maldon and Chelmsford) were in the archdeaconry of Essex. Any testator with land in only one archdeaconry had their will proved in that archdeacon’s court (and therefore, now their original wills are held by Essex Record Office). However, testators with land in more than one archdeaconry had theirs proved in the London Consistory Court (i.e. the official copies of their wills will be held by the London Metropolitan Archives in London). Therefore, many wills for the years 1520 to 1559 are missing for parishioners who were the ‘middling sort’ or elite (i.e. they owned land/property in both Great Dunmow and neighbouring villages or towns). The missing registers almost exactly span the offices of two incumbents of the bishopric of London: Cuthbert Tunstall, bishop 1522 to 1530(6) ; and John Stokesley, bishop 1530 to 1539(7). It could be speculated that the missing volumes were lost not long after these dates, perhaps handed over to the Elizabethan martyrologist, John Foxe, for his examination of early martyrs within the diocese of London.(8)

There is evidence within Great Dunmow’s Henrician churchwardens’ accounts which can also be used for will analysis. These accounts document six gifts of money from named parishioners to the church, but the wills from these people have not survived. However, as these donations were likely to have originated from wills, they have been included within this analysis. For example, vicar Robert Sturton’s missing will would undoubtedly contain a bequest to the church, as there is a 1528 churchwardens’ accounts entry ‘of[f] wylyem sturton of ye gyfte of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche…liijs iiijd [53s 4d]’(9). The churchwardens were diligent in recording bequests and gifts to the church in their accounts. This can be detected from John Skylton’s will of 1533 in which he left a bequest of 13s 4d to the church. This exact amount duly appeared in that year’s churchwardens’ accounts, given to the churchwardens by his wife.(10) Therefore, there is credibility to include gifts recorded within the churchwardens’ accounts within this analysis of wills.

Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘.

Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘.

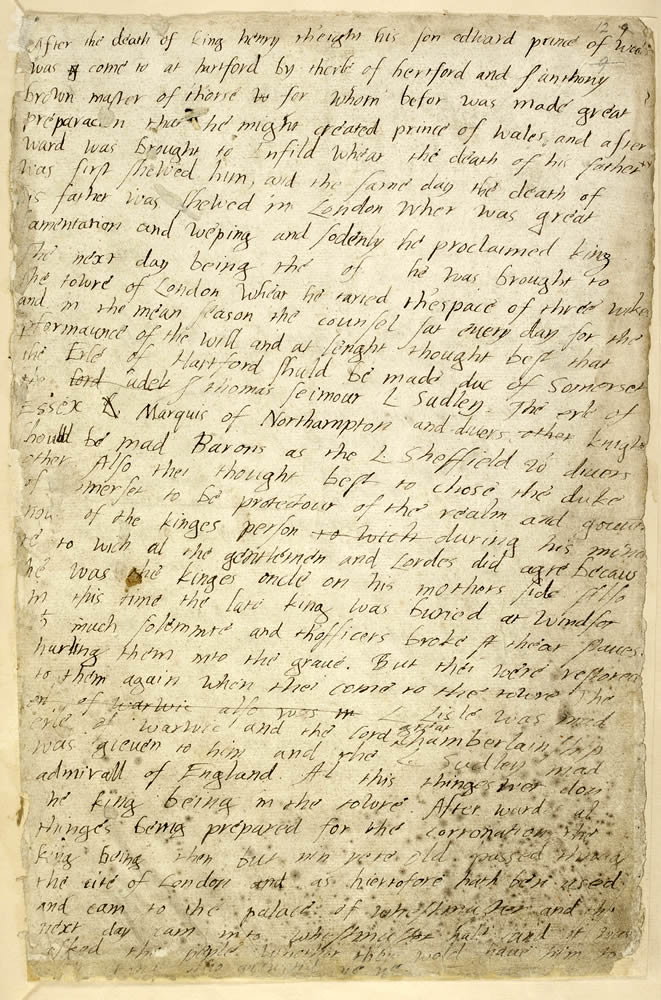

Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘.

Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘.

And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

Analysis of Soul Bequests

[The table below for soul bequests was originally on an A3 sheet of paper. I have had to shrink it so that it fits this blog post. Click it to display it within a new window and then use your zoom facility to increase the size of the text. The wills for Elizabeth’s reign are only up until 1565 as this is the point my dissertation ended.]

Soul bequests within preambles of wills have been used by historians of Reformation England to ascertain religious changes. A Catholic preamble would include words similar to ‘almyghtie god & to our blyssed lady saynt mary the virgyn & to all the holy company of heaven’(11). An evangelical or Protestant might include words such as ‘Almighty God and his only Son our Lord Jesus Christ, by whose previous death and passion I hope only to be saved’(12). Somewhere in between would be other types of soul bequests. Litzenberger divided her wills into three major categories: ‘Traditional’ [i.e. Catholic], ‘Ambiguous’, and ‘Protestant’, and within these categories, wills were further sub-divided. Litzenberger’s categories have been used as a framework for the analysis of soul bequests for Great Dunmow’s wills; as demonstrated in Table 2. Categorising soul bequests have to be handled with caution. Wills were only ambiguous if there were no other bequests indicating that they were traditional. Some wills contain either a final stipulation to the executors to provide for the wealth/health of the testator’s soul, or the bequest for ‘tithes forgotten’. The existence of either clause, it can be argued, was the sign of a traditional will, as discussed below. Moreover, ambiguity might have been a defence employed by traditionalists against an increasingly hostile environment.(13) This strategy of ambiguity by traditionalists might account for the eight ambiguous Edwardian wills made during evangelical vicar Geoffrey Crisp’s time. Furthermore, a Protestant was unlikely to use an ambiguous soul bequest and would almost certainly proclaim their religion in unmistakable language.(14) Table 2 demonstrates there were no unquestionably Protestant soul bequests within the surviving wills of Great Dunmow.

Analysis of other bequests (not family)

There are other limitations when using wills for the analysis of religious belief. Duffy comments ‘wills tell us more about the external constraints on testators than they do about shifting private belief.’(15) External constraints could be the religious policy imposed by the monarch, for example, the Edwardian denouncement of purgatory, trentals and masses.(16) There were other constraints, including the scribe who wrote the will and the testator’s witnesses. Margaret Spufford, in her work on sixteenth and seventeenth century wills was the first historian to observe a will could be written by a scribe.(17) She stated

A man lying on his death bed must have been much in the hands of the scribe writing his will. He must have been asked specific questions about his temporal bequests, but unless he had strong religious convictions, the clause bequeathing the soul may well have reflected the opinion of the scribe or the formulary book the latter was using, rather than those of the testator. (18)

Some wills indisputably demonstrate the testator had not been influenced by a scribe or witness. Great Dunmow’s Marian will of Thomas Baker contains a traditional soul bequest along with bequests for tithes forgotten; and, even more revealingly, an obit and a solemnly sang dirge.

A priest providing Extreme Unction (the Last Rites) to a man in bed, from Pontifical; Tabula (England, 1st quarter of the 15th century), British Library’s shelfmark Lansdowne 451 f.234.

There is evidence of a Henrician scribe who was active in two 1520s wills from Great Dunmow, and he possibly used a book containing standard formulaic clauses. This type of precedent book was not unusual during the Tudor period.(19) The will of widow Clemens Bowyer, dated February 1526, almost exactly mimics the earlier will of John Wakrell (October 1525). Both wills have the same soul bequests (Catholic, as would be expected from this period); along with bequests to the high altar, to Saint John’s gild, to the church’ torches, and to the ‘moder holy chyrch of polye [St Paul’s] in London’. Both wills have a bequest for an ‘honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol & all crysten solls yn ye p[ar]rsche churche’. However this is crossed out in Bowyer’s will. It is possible the scribe copied the wording from his precedent book, and Bowyer made him cross it out. Trentals were a series of 30 Masses performed within one year, with three Masses on each of the ten major feast-days of Christ and Mary; the priest also had to perform other liturgical duties throughout the year.(20) This was a substantial undertaking, as demonstrated by Wakrell’s bequest of 10s for his trental. Maybe Bowyer did not have sufficient funds, and so made the scribe delete the bequest. This scribe was probably the parish priest, Sir William Wree who was witness to these and one other will. Also witness to Wakrell’s will was former vicar, Robert Sturton, described as ‘p[ar]rsche prest’. Sturton had resigned as vicar in 1523, so he was still performing some of his previous clerical duties.

Will of John Wakrell of Great Dunmow (October 1525), Essex Record Office D/ABW 39/7. The trental bequest reads (from the second word): ‘It[e]m I be q[u]esthe [bequeath] unto an honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol [soul] & all crysten [Christian] solls [souls] yn ye p[ar]iche chyrch \of D[u]nmowe a fore sayde xs [10s]’.

Will of John Wakrell of Great Dunmow (October 1525), Essex Record Office D/ABW 39/7. The trental bequest reads (from the second word): ‘It[e]m I be q[u]esthe [bequeath] unto an honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol [soul] & all crysten [Christian] solls [souls] yn ye p[ar]iche chyrch \of D[u]nmowe a fore sayde xs [10s]’.

Will of Clemens Boywer [Bowyer] of Great Dunmow (February 1526), Essex Record Office D/ABW 3/8. The first crossing out is the trental: ‘It[e]m I bequethe to han [sic] honest prest to sy [n] ge [sing] a try[n]tall [trental] yn ye p[ar]rshe of myche [Much i.e. ‘Great’] D[u]nmow aforsad’. (Were pre-Reformation priests anything other than ‘honest’?)

Will of Clemens Boywer [Bowyer] of Great Dunmow (February 1526), Essex Record Office D/ABW 3/8. The first crossing out is the trental: ‘It[e]m I bequethe to han [sic] honest prest to sy [n] ge [sing] a try[n]tall [trental] yn ye p[ar]rshe of myche [Much i.e. ‘Great’] D[u]nmow aforsad’. (Were pre-Reformation priests anything other than ‘honest’?)

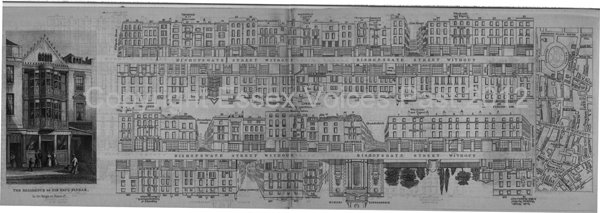

Old St Paul’s Cathedral – the ‘moder[mother] holy chyrch of polye [Paul] in London’ mentioned by 7 testators of Tudor Great Dunmow. St Paul’s was the mother church of the Diocese of London, and this diocese included the parish of Great Dunmow. The cathedral was the largest church in England and had the tallest spire in England. The spire was struck by lightning in 1561 and not replaced. St Paul’s was destroyed in 1666 – a casualty of the Great Fire of London. Sir Christopher Wren designed the new cathedral – one of the iconic images of today’s London.

Witnesses to Wills

The vicars and priests of the parish were witnesses to many wills. However, the decline in priests as witnesses demonstrates fewer priests were within the parish after Henry VIII’s break with Rome. Sir Edmund Clarke was witness to three traditional wills in the 1530s. Evangelical vicar Crisp, was witness to two Edwardian wills in 1551 and 1553; both with ambiguous soul bequests to ‘almighty god, my maker and redeemer’. Catholic vicar John Bird was witness to one traditional Marian will. The vicars must have witnessed many wills and surely influenced some testators by imposing their own beliefs on their dying parishioners. However, Elizabethan vicar, Richard Rogers, a former Protestant exile who spent Mary’s reign in Frankfurt,(21) did not enforce his beliefs on the wills of his parishioners. Seven Elizabethan wills were written during his tenure, although he was not witness to any of them. None of these wills were unequivocally and unmistakably Protestant: indeed the 1563 will of Gilbert Cooke had a traditional soul bequest including ‘the blesyd company of heavne’.

Priest administering last rites

from The Dunois Hours (Paris, c. 1440 – c. 1450 (after 1436))

British Library’s shelfmark Yates Thompson 3 f.211 .

The limitations of using wills to determine religious belief

Wills do not always accurately reflect the complete representation of a testator’s religious beliefs. In an investigation of late Medieval wills for All Saints, Bristol, the author of the study found the wills of some of the elite did not include bequests to the parish church.(22) However, the parish’s Church Books demonstrate that during these testators’s lifetime, substantial gifts, such as gilding of the Lady altar, and the refurbishment of the rood loft, had been made to the church. Furthermore, a wife often made donations after her husband’s death but during her lifetime, on behalf of them both. This generosity would most likely not have appeared in either the husband’s or his widow’s wills. This discrepancy between a testator’s will and the gifts made during their lifetime is also true within Great Dunmow. For example, Miles Docleye’s Edwardian will of 1551 has an ambiguous soul bequest and only bequests to his family; there are no religious bequests. It would appear his will was ambiguous but conforming to Edward’s Protestantism. However, Docleye, who must have been at least in his 50s when he died, had given money to each of the parish’s seven collections for traditional religious items during the 1520s and 1530s. It is impossible to determine if his beliefs had changed or if his will was conforming to Edwardian policy. It was probably the latter. This one example demonstrates that the analysis of wills for religious beliefs has its limitations. The laity of Great Dunmow had been investing in traditional religious artefacts throughout the 1520s and 1530s, but these donations are not apparent from their wills.

The importance of ‘tithes negligently forgotten’

The bequest to the high altar for ‘tithes negligently forgotten’ clause was an important part of pre-Reformation wills; and all ten Henrician wills have this bequest. One of the duties of the parish priest was to pronounce the Great Excommunication or General Sentence to his parishioners four times a year.(23) This proclaimed transgressions against the church; and debts (including unpaid tithes) were such transgressions. The bequest ensured the testator cleared his or her debt to the church and so their soul could benefit from prayers. Furthermore, unpaid debts meant the testator’s soul would be longer in purgatory, so this was an important bequest for traditional religion. Henry VIII banned the reading of the General Sentence in parish churches because it was vehemently against those who appropriated Church property or contested the authority of the Church(24), and, of course, Henry VIII had unquestionable contested the Pope’s authority in England.

This prohibition, along with the Edwardian theological retreat from the concept of purgatory,(25) was perhaps the reason why none of Great Dunmow’s Edwardian wills have the tithes to the high altar bequest. Moreover, the Great Dunmow’s high altar had been destroyed on the orders of Edward VI.(26) However, four Marian wills do have the clause; of these, three also have a traditional soul bequest. These four wills were written in 1557 and 1558; so it is possible this bequest was not included in earlier Marian wills because Great Dunmow’s high altar was still to be rebuilt after Catholic Mary came to the throne of England. In Elizabeth’s reign, Elizabeth Dygbey’s will written in December 1558 (i.e. one month after Mary’s death), also had a traditional soul bequest, along with the tithes clause. This was before the Marian high altar was taken down sometime between 1559 and 1561.(27) In 1564, John Byckner used a variation of the tithes bequest for a will which was otherwise ambiguous; the high altar had again been destroyed, so he left his money for ‘tithes forgotten’ to the ‘curate’. Byckner’s will is unusual because, apart from Dygbey’s will written shortly after Mary’s death, no other early Elizabethan will contains the tithes bequest. If this John Byckner, a wax chandler, was the same John Byckner, who lived in the High Street in 1525-6,(28) he would have been at least in his 60s and so perhaps had some of the old, traditional habits. This confirms the remark, ‘Wills were made usually by the old, who were generally less open to new ideas than the young or middle aged.’(29)

A priest excommunicating a group of people by raising a candle

from Omne Bonum (Ebrietas-Humanus) (London, England, c.1360-c.1375)

British Library’s shelfmark Royal 6 E VII f.75v.

Conclusion

The analysis within this articles has demonstrated that bequests within wills alone cannot substantially confirm the religious faith of a testator. However, it is clear that collectively the wills of Great Dunmow do demonstrate significant changes over time. Bequests to the church almost totally stopped after Henry VIII’s reign, in all probability because his attack on traditional religious artefacts made parishioners cautious. Not a single Edwardian testator made an unequivocally Protestant will, even with evangelical vicar Crisp present. Mary’s reign demonstrated a shift back towards traditional religion, with bequests to the high altar, and obits. The early years of Elizabeth’s reign demonstrate that wills had once again started to move away from traditional bequests. However, external factors could influence a testator’s will, for example, religious changes enforced by the monarch, local vicars, scribes and witnesses, and the age of the testator. Therefore wills cannot provide the complete account of the parishioners of Great Dunmow’s changing beliefs. Moreover, Henrician and Marian anti-Catholic events did take place in the parish with the 1546 re-enactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton, and Thomas Bowyer’s disobedience to the re-established Catholic Church. Therefore, wills can provide only a limited narrative regarding the changes experienced by this parish during the Reformation.

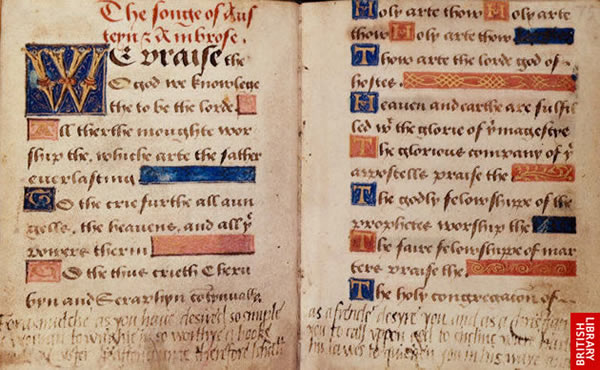

Details of a funeral

from Book of Hours, Use of Sarum

(England, S. E. (Suffolk, Bury St Edmunds?), 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 15th century)

British Library’s shelfmark Arundel 302 f.77v.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

Footnotes

(1) Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (2nd edn., 2005), pp.515-21.

(2) Caroline Litzenberger, The English Reformation and the Laity: Gloucestershire, 1540-1580 (Cambridge, 1997), pp.168-178.

(3) (n/a to this blog)

(4) This includes six monetary gifts, as documented in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, but a corresponding will has not survived.

(5) London Metropolitan Archives, Diocese of London Consistory Court Wills index (2011), (At the time of writing my dissertation, these indexes were in pdf file format and online at http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. However they do not appear to be there at present.)

(6) D. Newcombe, ‘Tunstal, Cuthbert’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition, May 2011), http://www.oxforddnb.com

(7) Andrew Chibi, ‘Stokesley, John’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition, May 2011), http://www.oxforddnb.com

(8) Personal correspondence, Richard Rex, Cambridge, March 2011.

(9) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.7r.

(10) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fol.18v.

(11) Will of Katherine Smythe (1558), Essex Record Office, D/ABW/33/335.

(12) Margaret Spufford, ‘The Scribes of Villagers’ Wills in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and their influence’, Local Population Studies (1972), pp.28-43 at 29.

(13) Correspondence, Rex.

(14) Correspondence, Rex.

(15) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, p.508.

(16) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, p.505.

(17) Margaret Spufford, Scribes of Villagers’ Wills, pp.28-43.

(18) Margaret Spufford, Scribes of Villagers’ Wills, p30.

(19) Correspondence, Rex.

(20) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.370-371.

(21) Christina Hallowell Garrett, The Marian Exiles (Cambridge, 1966), p.273.

(22) Clive Burgess, ‘”By Quick and by Dead”: Wills and Pious Provision in Late Medieval Bristol’, The English Historical Review, 102 (October 1987), pp.837-858 at p.842.

(23) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.356-7.

(24) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.356-7.

(25) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.504.

(26) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.40v.

(27) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.44v.

(28) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.2v.

(29) Robert Whiting, Local Responses to the English Reformation (Basingstoke, 1998), p.130.

(30) The first two columns of Table 2 have been taken from Caroline Litzenberger, The English Reformation and the Laity: Gloucestershire, 1540-1580 p.172

Notes

Great Dunmow’s original churchwarden accounts (1526-1621) are in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Please subscribe to my newsletter using the link below

I am planning exciting events during 2019 – including unique online courses:

- If Walls Could Talk – Uncover the secret history of your home: step-by-step, discover how to research the story of your home through time;

- The Witches of Elizabethan and Stuart Essex: uncover the myths and truths about witches of the 16th and 17th centuries and society’s attitude towards them.

My newsletter will give you more details about all my events, courses, talks and local history services.

You can also connect with me on Facebook and Twitter

Twitter: EssexVoicesPast

Facebook: Kate J Cole

| Post created 2013 and updated September 2019 © Kate J Cole | Essex Voices Past™ 2012-2019 |

Edward VI’s diary

Edward VI’s diary Frontispiece with the arms of Edward VI, Shelfmark: Royal 16 E XXXII f.1v,

Frontispiece with the arms of Edward VI, Shelfmark: Royal 16 E XXXII f.1v, Tallis’s Street View of Bishopsgate Without.

Tallis’s Street View of Bishopsgate Without.  Great Dunmow (Donemowe)

Great Dunmow (Donemowe)