Thomas Bowyer, weaver and martyr of Great Dunmow d.1556

Today, 27th June, is the anniversary of the burning of thirteen people at Stratford le Bow in 1556, executed in the most horrible manner because of their religion and faith. It was the largest burning of a group of people in Tudor history, and this terrible spectacle was watched by a crowd of over 20,000 people.

Burning of 13 people (11 man and 2 woman) at Stratford le Bow June 1556,

Burning of 13 people (11 man and 2 woman) at Stratford le Bow June 1556,

from John Foxe, Acts and Monuments (1570 edition), p2135.

The story regarding this terrible burning in London is being retold today by myself on Spitalfields Life blog here. The story of one of those victims who perished in Queen Mary Tudor’s flames, Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow is retold here at Essex Voices Past.

Piecing together details about these men and women is difficult because, apart from John Foxe’s book, there is not much surviving contemporary evidence, particularly as these were not high-profile victims. However, during my research of Tudor Great Dunmow, I have been able to piece together circumstantial evidence regarding the background of Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow.

According to John Foxe’s 1563 version of The Acts and Monuments (more commonly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs),

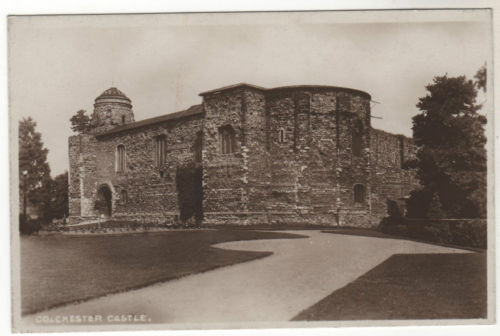

Thomas bowyer sayde he was brought before one maister Wiseman of Felsed, and by him was sent to Colchester castel, and from thence was caryed to Boner Byshop of London, to be by him further examined.

Colchester Castle – county gaol of Tudor Essex

Colchester Castle – county gaol of Tudor Essex

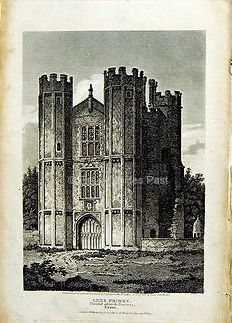

Felsted is the neighbouring village to Great Dunmow and Master Wiseman was probably the local JP whom Bowyer was hauled before. It is curious that Bowyer was not taken to the magistrates in Essex’s county town of Chelmsford. However, there is possibly a reason for this (or rather, a person): Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich. Lord Rich, that arch-villain of Tudor history, was an enthusiastic persecutor of Essex Protestant heretics during the Marian years. This enthusiasm was in spite of his earlier zealous support of Henry VIII’s break from Rome (resulting in his betrayal of Sir Thomas More), and his support of Edward VI’s Protestant religious changes. One of Rich’s many manors included his great mansion, Leighs Priory, (located a very short distance from Felsted) a former religious house granted to him by Henry VIII at its dissolution in 1536. Thus, Rich had very strong connections to Felsted and was buried in the parish church in 1567. With the presence of Lord Rich in Felsted, this must have been the reason why Bowyer was taken there, and not to magistrates in Chelmsford. Foxe did record that another victim who died alongside Bowyer, George Searle from White Notley (a village a couple of miles from Felsted), was taken before Rich. So the supposition that Richard Rich was involved in the case of Thomas Bowyer is entirely plausible.

Leighs Priory, Felsted (also known as Lees and Leez),

Leighs Priory, Felsted (also known as Lees and Leez),

home of Richard Rich, Lord Rich

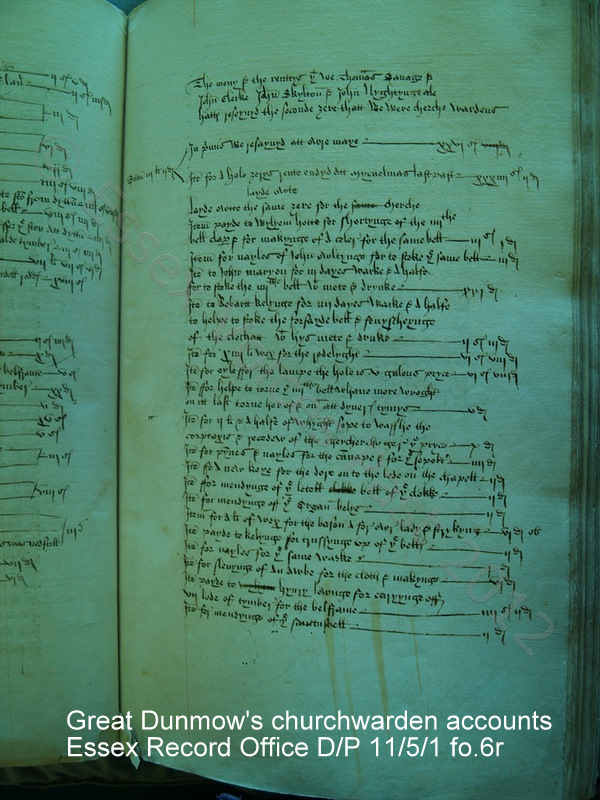

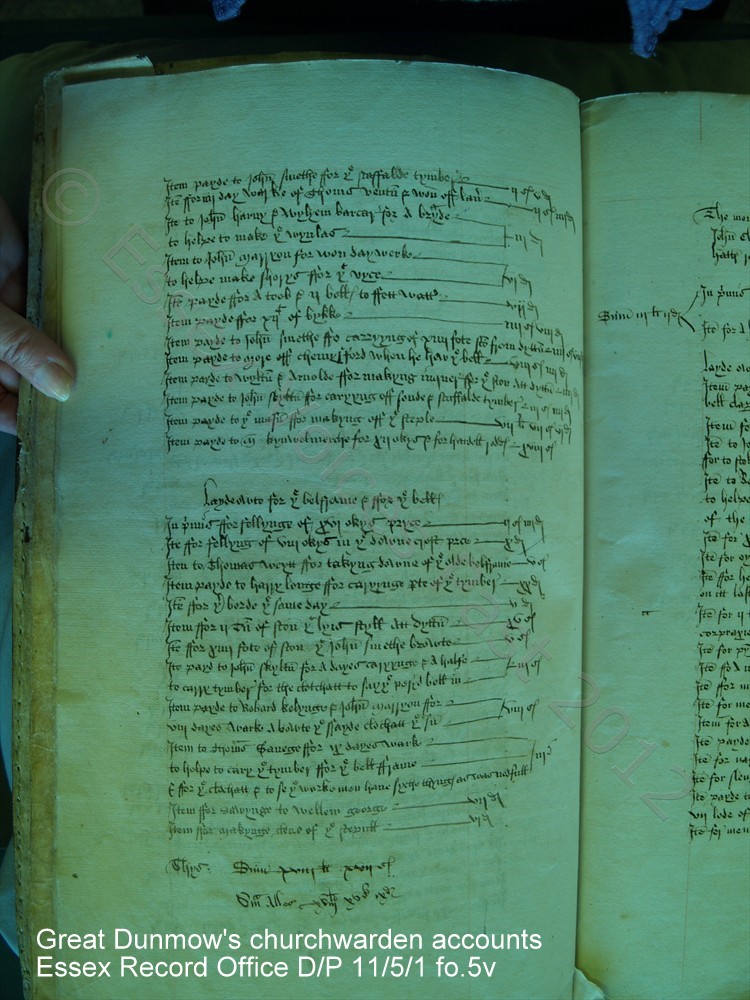

That the small North Essex town of Great Dunmow had produced a weaver with such strong and unshakeable Protestant convictions is, on the surface, remarkable. However, the parish of Great Dunmow had already visibly demonstrated that many townsfolk supported Henry VIII’s break with Rome. This evidence is contained within an extraordinary folio of Great Dunmow’s beautifully tooled leather-bound churchwardens’ accounts, now in the care of Essex Record Office.

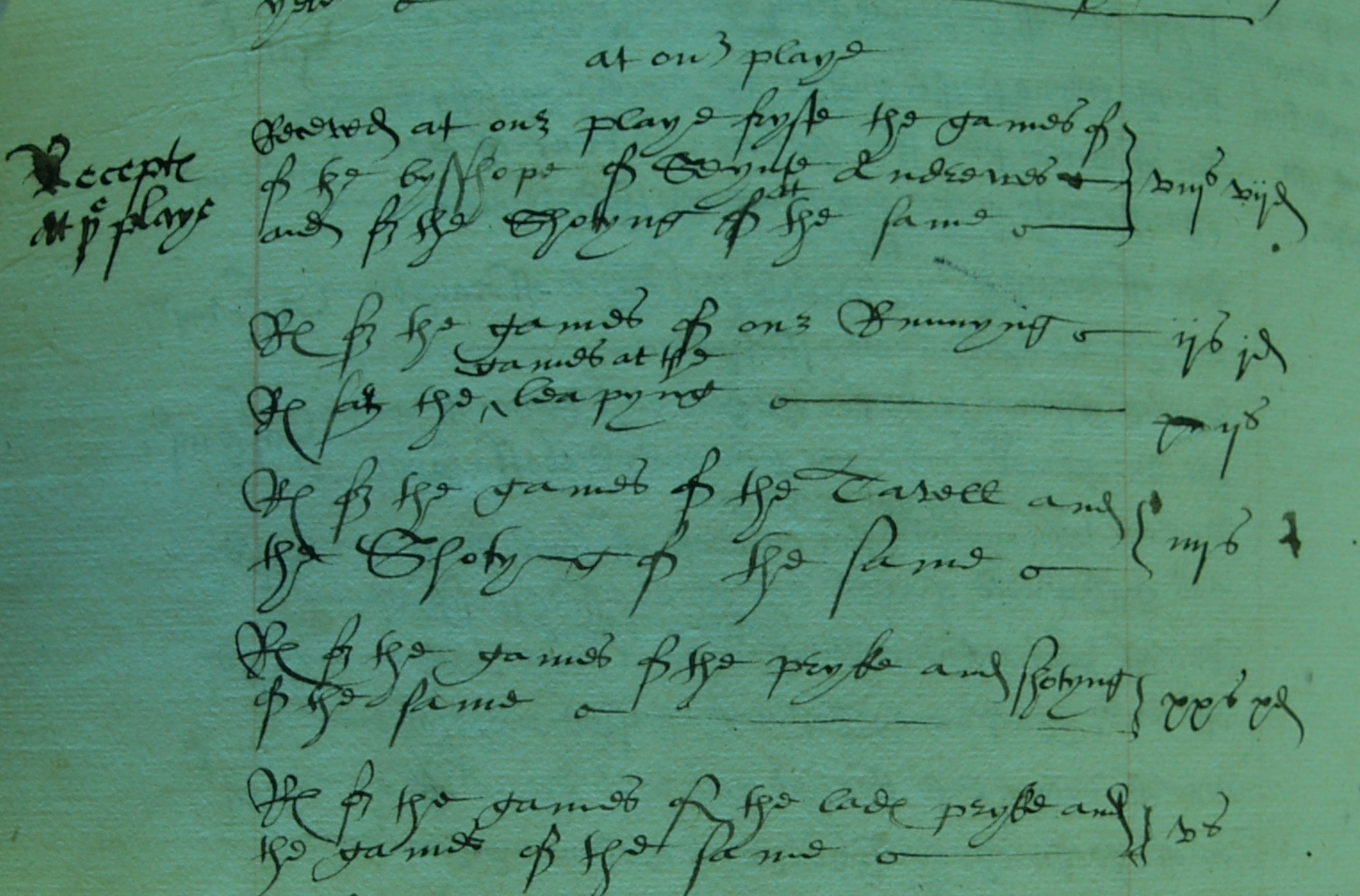

In the summer of 1546 (the final summer of Henry VIII’s life and reign), the townsfolk of Great Dunmow staged a remarkable anti-papist event involving the entire parish. It is very likely that an impressible 16 year old Thomas Bowyer was also present. This event took place during the parish’s annual Corpus Christi religious play when people from the neighbouring towns and villages came into Great Dunmow for the communal celebration of this Catholic religious feast-day. The churchwardens’ accounts itemise receipts for that year’s Corpus Christi play, followed by the money received from each named local village who attended the play (eleven villages in total).

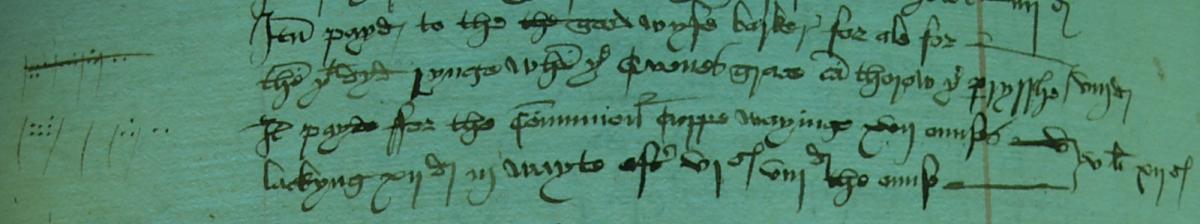

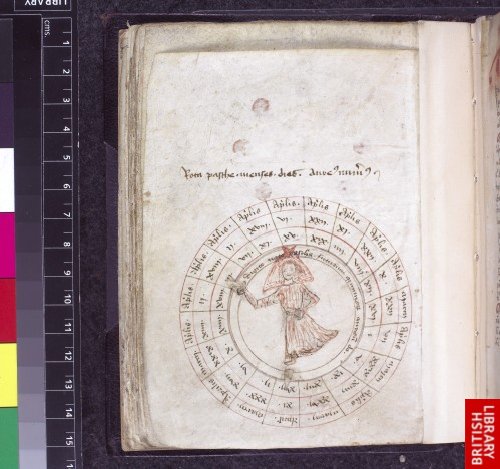

Entries for Great Dunmow’s June 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day

Entries for Great Dunmow’s June 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day

(Essex Record Office, D/P 11/5/1 f.39v)

[heading] At our playe

[in the margin] Recepte at ye playe

Receved at our play & fryste the games of of [sic] the bysshope

of saynte andrews and for the shottyng of at the same viijsvijd

Rec for the games of our runnyng ijsid

Rec for the \games at the/ leapyng ijs

Rec for the games of the casell and the shotyng of the same iiijs

Rec for the games of the pryke and shotyng of the same xxsxd

Rec for the games of the lade pryke and the games of the same vs

Deciphering this entry demonstrates that the people of Great Dunmow and surrounding villages had held an archery competition (the ‘shottyng’) which included shooting bows and arrows against an effigy of the Archbishop of Saint Andrews and at a structure which resembled the Archbishop’s Scottish castle (the ‘casell’). The ‘prykes’ were archery targets set at a specified number of paces away from the archer.

The reason for the staging of this remarkable event was because of a personal grudge of Great Dunmow’s evangelical vicar, Geoffrey Crispe MA, against Cardinal David Beaton. Beaton was the Catholic archbishop of Saint Andrews and the highest ranking cleric in a then Catholic Scotland. He had been murdered by Scottish Protestants in May 1546, three weeks previously to the feast-day of Corpus Christi, and his castle seiged. Beaton’s murder and the storming of his castle in Saint Andrews was in direct retaliation for him burning at the stake the Protestant Scottish martyr George Wishart a few months previously. Prior to his Protestant teachings in Scotland, George Wishart had been a lecturer at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge – the same college and university where Great Dunmow’s vicar, Geoffrey Crispe, had studied and had been a fellow. The vicar of Great Dunmow, Geoffrey Crispe, was a contemporary, friend and associate of Protestant George Wishart.

Three weeks after the murder of Cardinal Beaton and 450 miles away, Great Dunmow used that year’s Corpus Christi feast-day to reenact his murder and the storming of his castle. An event which must have been instigated and supported by Wishart’s friend and colleague, vicar Geoffrey Crispe. This very public celebration of the cardinal’s murder demonstrates that by 1546 there was very strong anti-Pope (and probably anti-Scottish) feeling within Great Dunmow. Moreover, as Beaton’s murder was welcomed by the English king, Henry VIII, the town was visibly demonstrating their loyalty to their monarch. This folio within Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts contain the only evidence for this event, so it cannot be determined if the motivation behind the celebrations was inspired by Crisp’s personal affiliations to Wishart, or the parish’s loyalty to their sovereign, or their changing religious theology. It was probably a combination of all three.

George Wishart (b. c1513, d. 1 March 1546)

Cardinal David Beaton,

archbishop of Saint Andrews

(b. c1494, d. 29 May 1546)

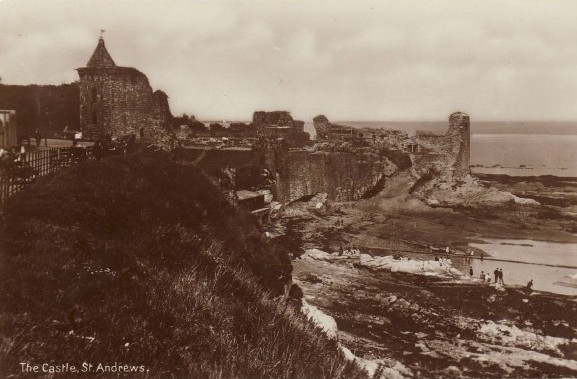

Ruins of Cardinal Beaton’s castle in St Andrews, Scotland.

St Andrews’ castle – laid siege by Scottish Protestants in retaliation for the burning of George Wishart. The English parish of Great Dunmow and its neighbouring villages re-enacted the storming of this castle three weeks later.

It is likely that an impressionable 16 year old Thomas Bowyer had been present at the reenactment of the shooting of Catholic Cardinal Beaton and the storming of his castle. Furthermore, it is also probable that he was one of those young lads who took part in the ‘games of the lade pryke and the games of the same’. These activities during Corpus Christi 1546 was a clear demonstration of the anti-papist feelings within the parish of Great Dunmow, and its surrounding villages. Moreover, vicar Geoffrey Crispe had embraced these religious changes to such an extent that at some point during his 1540 to 1554 tenure of the living of Great Dunmow, he had married and so had a wife. Many parishioners, led by vicar Crispe, had started to embrace Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the changing religious wind blowing through England. However, in June 1556, ten years after Great Dunmow’s anti-papist Corpus Christi feast-day, Thomas Bowyer was burnt at the stake in Stratford le Bow in punishment for being a Protestant. The winds of religious change (Catholic this time, led by the Pope in Rome), instigated by a Tudor English monarch, had once more blown through England and reached the north Essex parish of Great Dunmow.

The narrative about Great Dunmow’s reenactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton possibly explains why Thomas Bowyer had such strong Protestant convictions: he had probably learnt some of his faith through the parish’s anti-papist married vicar, Geoffrey Crispe. But who exactly was Thomas Bowyer of Great Dunmow, and how did he come to the attention of Bishop Bonner?

The Bowyer family of Great Dunmow occur within approximately ten legal documents, from 1483 to 1529, now held by Essex Record Office. The majority of these documents relate to land located near the parish church of St Mary the Virgin. Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts also contain numerous entries from the reign of Henry VIII for various Bowyers. These entries include a 1536-7 gift from ‘old Thomas Bowyer’ of 3s 4d (possibly a bequest from his, now lost, will) and entries for Mother Bowyer of Parsonage Downs, and Richard Bowyer of Church End. Parsonage Downs and Church End are two locations within Great Dunmow near the parish church. Richard Bowyer was a tenant of church land from at least the 1530s and paid yearly rent to the church, as recorded in churchwardens’ accounts. The final entry for the payment of his rent occurred in the early years of Edward VI’s reign: Richard Bowyer’s tenancy of church land must have been terminated at the time of the 1547-8 crown investigations into church lands. The Bowyer family are also documented within Henry VIII’s 1523-1524 Lay Subsidy returns for Great Dunmow: Clemens Bower (the ‘Mother’ Bower in the churchwardens’ accounts) had goods to the value of £6 and paid 3d in taxes, and Johanne (or, more likely, John) was assessed at 26s 8d and paid 4d.

The records prove that the Bowyer family of Great Dunmow were of the middling sort and were tenants of church land. No records exist to connect the martyr Thomas Bowyer to these Bowyers and he is not named in the churchwarden accounts. However, it is possible that the ‘Old Thomas Bowyer’ documented in the accounts was the martyr’s close relation (perhaps his father). Moreover, a few hundred yards away from Richard Bowyer’s tenement at Church End and just past the area still known to this day as Parsonage Downs where Mother Bowyer lived, is a bridge over the River Chelmer called ‘Bowyers Bridge’. This is said locally to be so named to commemorate the Protestant martyr, Thomas Bowyer. The date when the bridge became named is unknown. However, its close proximately to the land tenanted by the Bowyer family cannot be coincidence.

Bowyers Bridge, on the way to Little Easton c1901-1910

If the martyr, Thomas Bowyer, was related to Richard Bowyer, tenant of church property, and the Old Thomas Bowyer who left money in his will to the parish church, then he would have been well-known to the vicars of Great Dunmow. By the time of Thomas Bowyer’s martyrdom in 1556, anti-papist vicar Geoffrey Crispe had been deprived of the parish of Great Dunmow (because of his marriage). The next vicar of Great Dunmow was Catholic Doctor John Bird – the former Bishop of Chester – who had been deprived of his bishopric because he had married during Edward VI’s reign. Bird, having cast aside his wife, arrived in Great Dunmow in 1554, and became the suffragan bishop (i.e. assistant) to the Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner. The same Bonner, who was the zealous oppressor and burner of Protestants within his diocese which included the parish of Great Dunmow.

Furthermore, because of an unfortunate incident by the vicar, which took place in front of Bishop Bonner in the parish church of Great Dunmow in July 1555, Bird would have been anxious to show Bonner his Catholic allegiance. For this story, we once again turn to the Elizabethan martyrologist, John Foxe, who gave a heavily biased account of this incident in an unpublished manuscript (Harleian MS 42 f.1r-v). According to Foxe, Bird’s sermon that day in front of Bishop Bonner was about the text ‘Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam’ (‘Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church’). Bird’s intention was to ‘prove the stability of St. Peter, and so successively of the Pope’s seat; but unfortunately wandered away into the account of St. Peter’s fall’ (W T Scott, Antiquities of an Essex Parish: Or Pages from the History of Great Dunmow (1873) p57). Bonner was infuriated by this anti-papist sermon and

stood upon thorns, for he made face, his elbows itched, and so hard was his cushion whereon he sat, that many times during the sermon he stood up looking towards the suffragane, giving signs (and such signs as almost had speaking) to proceed to the full event of the cause in hand. (Harleian MS 42 quoted in Scott, p57.)

The outcome of this disastrous sermon was that vicar Bird broke down to the great distress of the parish’s Catholics and the jubilation of the Protestants (Scott, p58). Vicar Bird must have been an old man in his 60s at this time, and had lived through so many religious changes. So the direction this sermon took was probably caused by the ramblings and forgetfulness of an old man. Therefore, despite Foxe’s insinuations, this sermon was probably not a deliberate attempt to displease Bishop Bonner or to show Protestant beliefs. However, the sermon had displeased Bishop Bonner and vicar Bird probably would have done anything to restore himself to Bonner’s favour.

It is therefore little wonder that Thomas Bowyer of Great Dunmow, whose family had been in the parish since at least the 1480s, came to the attention of the authorities. With Bishop Bonner’s loyal assistant, Dr John Bird, being the Catholic vicar of Great Dunmow, and Lord Rich living nearby in Felsted, Thomas Bowyer would not have been passed over by the anti-Protestant tide of persecution for long. Hence, on 27th June 1556, Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow was burnt at the stake at Stratford le Bow in London alongside 10 men and 2 women.

Modern-day plaque on Bowyers Bridge, on the main road from Great Dunmow to Thaxted by the turning for the village of Little Easton. The age of Thomas Bowyer on the plaque is incorrect: according to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Bowyer died aged 26.

Modern-day plaque on Bowyers Bridge, on the main road from Great Dunmow to Thaxted by the turning for the village of Little Easton. The age of Thomas Bowyer on the plaque is incorrect: according to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Bowyer died aged 26.

Notes on the ‘bishop of Saint Andrews’ in the churchwardens’ accounts

Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts has been much examined by historians of the Reformation, Corpus Christi plays and early-modern drama in England. However, the entries on folio 39v for the ‘bysshope of saynte andrews’ and ‘casell’ have been either incorrectly transcribed or misinterpreted. In the secondary literature, ‘casell’ has been transcribed as either ‘tavell’ or ‘tarell’, and then totally ignored, and the reference to the ‘Bishop of Saint Andrews’ has been totally misunderstood. One historian even asserted that the entry to the bishop meant that Great Dunmow was acting the masquerade of a boy-bishop. All historians who have analysed the churchwardens’ accounts have totally missed the connection between the vicar of Great Dunmow to the Scottish Protestant martyr, George Wishart. This connection explains why such an extraordinary event took place in Great Dunmow in June 1546. In the secondary literature, I have found no other references to an English parish celebrating the murder of the Scottish Catholic archbishop. My post today is the first time this connection, and Great Dunmow’s reenactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton during Corpus Christi feast-day 1546, has been made public. I discovered it in 2011 whilst researching for my Cambridge University master’s degree.

The historian’s craft of teasing evidence from sources

My main break-through came after I had told myself countless times that what I was reading HAD to make sense. The churchwarden accounts were the financial records of a parish church and therefore had to contain information about money either coming in or going out, along with the reason for the income/expenditure. Furthermore, the churchwardens’ accounts were an open record so could be read by any contemporary church or state official so had to make sense in that context. Indeed, Eamon Duffy has argued that it is likely many parishes’ churchwardens read their accounts out loud in front of their parish in a manner similar to a modern-day public meeting. Therefore, the language used in some churchwardens’ accounts imitates the behaviour of the spoken word (Eamon Duffy, Voices of Morebath, p23-4). So I read out-loud the entries about the bishop of Saint Andrews – and, once again, I heard our Tudor scribe’s Essex/Suffolk voice shining down through the centuries. However, I was somewhat startled when the scribe’s soft ‘casell’ came out of my mouth as a loud and clear ‘castle’! By reading the entry aloud, I had cracked the secret of this folio! After that breakthrough, and with a little more research into the men who were the Tudor vicars of Great Dunmow, everything else slotted into place.

The historical analysis techniques I used to decipher Great Dunmow’s 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day are discussed in the posts listed below.

– Interpreting primary sources – the 6 ‘w’s

– Primary sources – ‘Unwitting Testimony’

– Palaeography and reading between the lines

– The dialect of Tudor Essex

– Great Dunmow’s Tudor dialect

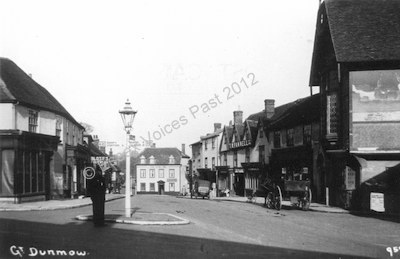

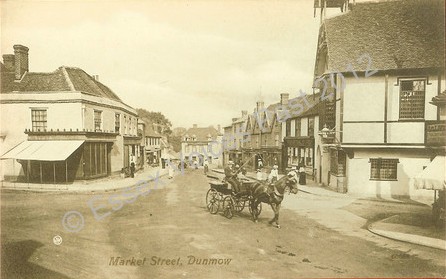

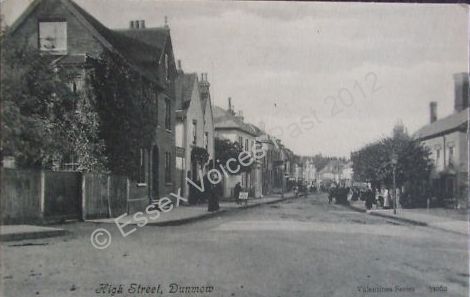

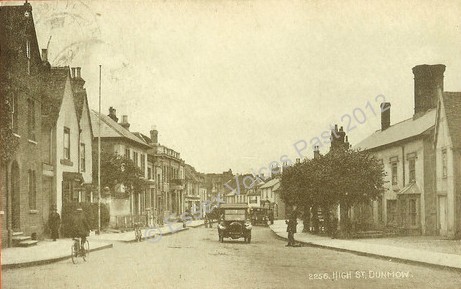

Parsonage Downs and Church End, home of the Bowyers of Great Dunmow

The pictures below are of Parsonage Downs (a small area of land located next to Bowyers Bridge) and Church End (a tiny hamlet next to the parish church). (Photos from 2012 and postcards from c1901-1910)

Parsonage Downs

Church End

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– The Tudor witches of Essex

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

– The craft of being a historian: Research Techniques

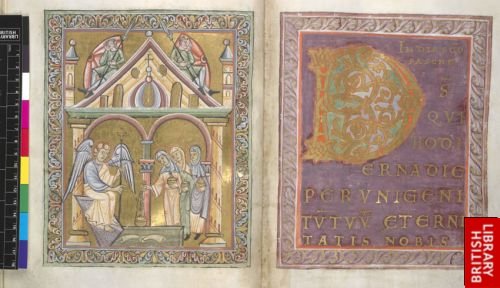

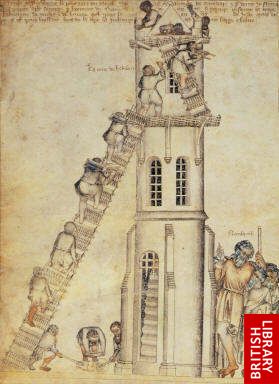

Luttrell Psalter, Psalm 79; Archers practicing at the butts

Luttrell Psalter, Psalm 79; Archers practicing at the butts

(East Anglia, England, 1325-35), shelfmark Add. 42130, f.147v, © British Library Board.

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

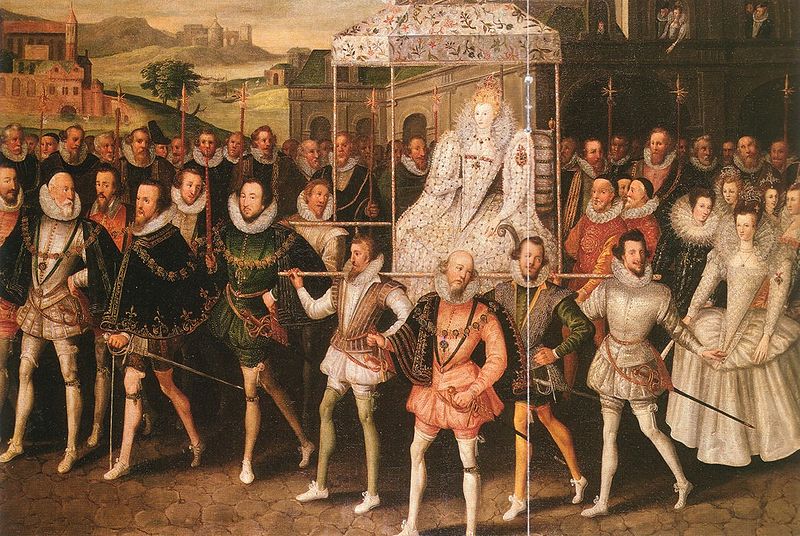

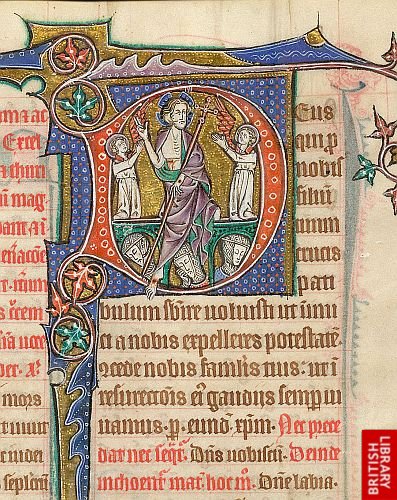

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569),

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569), © Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

© Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

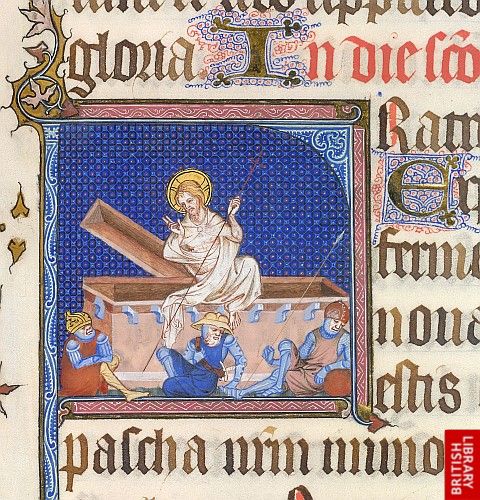

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

The beautiful Thaxted church, home of the yearly

The beautiful Thaxted church, home of the yearly